Stress is a sickness. You can’t catch it from a sneeze or a handshake, but it can still make you sick. Too much stress from your job, your relationships or even the evening news can have dire consequences on your health that manifest in physical ways too.

In 2020, for example, researchers at The Ohio State University discovered a link between stress and high blood sugar in people with type 2 diabetes.1 And in 2021, researchers at Emory University found that mental stress “significantly” increased the risk of cardiovascular events—including death, nonfatal heart attacks and heart failure—in patients with stable coronary heart disease.2 There have even been studies in mice that suggest stress can contribute to the growth and spread of cancer.3

“In people with chronic stress, we see high cholesterol, high blood pressure, angina, weight gain, sleep disturbance, osteoporosis—the list of diseases and health problems is endless, really,” says integrative cardiologist Mimi Guarneri, M.D., president of the Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine and co-founder and medical director of Guarneri Integrative Health Inc., an integrative medicine practice in La Jolla, CA. “In some cases, the problem is stress hormones that flood our body. In other cases, it’s our coping mechanisms—overeating, smoking, drugs, alcohol. People engage in all sorts of harmful addictive behaviors in order to deal with stress.”

On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 means you have “little or no stress” and 10 means you have “a great deal of stress,” the average American has a stress level of 5, the American Psychological Association (APA) reported in March 2022. Although that doesn’t sound terrible, 4 in 10 adults (41 percent) say their stress level increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.4 Among people’s most significant stressors, APA reports, are work (66 percent), money (61 percent), family responsibilities (57 percent), personal health concerns (52 percent) and relationships (51 percent), all of which have been challenged by the coronavirus, inflation and other current events.5

“We have real mental health effects emerging from this period of prolonged stress that we have to address now,” says APA CEO Arthur C. Evans Jr., Ph.D. “Pandemic stress is contributing to widespread mental exhaustion, negative health impacts and unhealthy behavior changes—a pattern that will become increasingly challenging to correct the longer it persists. It is urgent that as a nation we prioritize the mental health of all Americans.”

Integrative health experts like Dr. Guarneri say massage therapy could be part of the solution. After all, stress relief is one of the best-known and most-touted benefits of massage therapy. To be effective agents of stress management, however, massage therapists must understand what stress is, how it manifests in the body and what interventions might help their clients alleviate it.

What’s Behind Stress?

What seems emotional—you feel stressed out—is actually physiological, according to Ryan Gauthier, DAOM, LMT, who practices acupuncture and Chinese medicine at Henry Ford Health in Detroit.

“When humans face a challenge or threat, they have a partly physical response,” Gauthier says. “The body activates resources that help people either stay and confront the challenge or get to safety as fast as possible.”

In most cases, the body’s “fight-or-flight” response to stress is actually a good thing, says Lauren Fowler, Ph.D., associate professor of neuroscience at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville.

“There are two main types of stress that humans experience,” Dr. Fowler explains. “First, there’s an immediate stress response, which comes from adrenaline. If you’re hiking and a bear starts to chase you, you need to be able to get away from that bear. So your body activates the sympathetic nervous system, which is a functional response to help you get away from an immediate threat.”

Next, there’s a long-term stress response from the stress hormone cortisol. “Our cortisol response is designed to help us learn from stressors and prepare for them,” Dr. Fowler continues. “That’s the kind of stress we experience when we’re studying for a test, or when we start to think about paying our taxes every year at tax time. That’s good stress, because it helps us plan for the future.”

Good stress goes bad when people fixate on stressors, suggests integrative psychiatrist Henry Emmons, M.D., co-founder of the websites NaturalMentalHealth.com and JoyLab.coach, and author of The Chemistry of Calm: A Powerful, Drug-Free Plan to Quiet Your Fears and Overcome Your Anxiety.

“The ability to respond to threats in the environment is woven into all mammals. The problem with humans is that we can overthink things in ways that keep our natural fear and vigilance alive a lot longer than they should be,” Dr. Emmons says. “Our stress response is meant to last for a few minutes, or maybe a few hours. But when it goes on for days, weeks or months, then it can really become destructive.”

In other words, it doesn’t matter if the bear is still chasing you. If you keep replaying the memory in your head, your body assumes it’s still a threat. The consequences can manifest in each of its major systems:

Musculoskeletal system: Stress sends blood to your muscles so they will be ready to respond to threats. That causes them to tense up, according to Dr. Fowler, who says people with chronic stress may experience tension headaches and neck or back pain as a result of prolonged muscle tension.

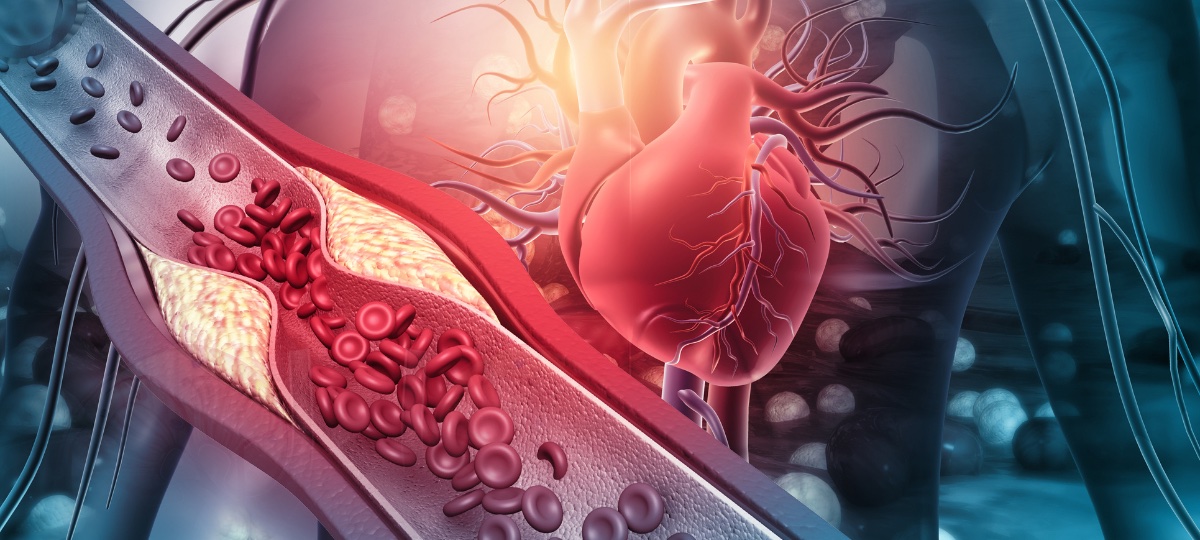

Cardiovascular system: Dr. Guarneri says heart rate and blood pressure rise during times of stress because the heart is trying to get blood—and blood sugar—to muscles and organs quickly, giving you ample energy to remain alert and responsive.

Respiratory system: Dr. Fowler says stress causes your respiratory rate to increase for the same reasons it causes your heart rate to increase: Breathing faster allows your body to get the oxygen and energy it needs to respond rapidly. This can lead to hyperventilation and shortness of breath.

Gastrointestinal system: When it’s under stress, your body shuts down functions that it doesn’t immediately need. Often, that includes digestion, according to Fowler, who says there’s no time to stop for a meal or a bathroom break when you’re running away from a bear. The impact of stress on digestion can cause constipation or diarrhea, she says. Appetite also can be affected. Adrenaline, for example, suppresses appetite while cortisol stimulates it.

Reproductive system: People who are chronically stressed have trouble reproducing, explains Dr. Fowler, who says a stressed-out body views reproduction in the same way it views digestion—as nonessential. In particular, stress can negatively impact erectile function and sperm production in men, menstruation and pregnancy in women, and sexual desire in all people.

Can Massage Help?

Although you can’t stop your body’s reaction to stress, you can manage and mediate it.

“There are always going to be stressors in life. What matters is how you react to those stressors,” says Dr. Fowler’s colleague Ann Blair Kennedy, LMT, BCTMB, DrPh, assistant professor of behavioral, social and population health sciences at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville. “Fortunately, there are lots of tools that we can put in the toolbox to help us deal with stress.”

Massage therapy is among them because of its positive impact on both body and mind, suggests Kennedy, who also serves as executive editor and editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Therapeutic Massage and Bodywork.

Its effect on the body is evident in measures like heart rate variability, she says. When the sympathetic nervous system is active, which it is during stress, heart rate variability is low. When the parasympathetic nervous system is active, which it is during rest and relaxation, heart rate variability is high. Although the sample size was small, a 2020 study by German researchers found that just 10 minutes of massage created “significant increases” in heart rate variability.6

There’s a long history of similar findings in scientific literature. A 2007 study from the University of South Florida, for example, showed that regular back massages significantly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure in patients with clinically diagnosed hypertension, a potential cause of which is chronic stress.7 A 1999 study in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies also found reduced blood pressure in hypertensive people who received massage.8 Again, sample sizes were small, but the collective strength of numerous studies over many years suggests real benefits.

Benefits could be further enhanced with the application of heat, suggests Dr. Emmons, who says warmth has been shown to calm tense muscles. In fact, a 2020 study in the Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation found that the local application of heat to trigger points reduces neck and foot pain by increasing muscle relaxation and tissue blood flow.9

The body may be able to influence the mind. “Stress is a temporary physical response, but we keep it alive through thinking,” Emmons explains. “If you can get the body to stand down from its state of emergency, the mind often follows.”

The reverse also can be true. “Anything you can do to disengage the thinking part of the brain for a little while can put the body into a state of relaxation,” Dr. Emmons continues. “You might not be able to directly turn off the body’s cortisol valve, but you can activate the parasympathetic nervous system by helping the body relax, which indirectly can help reduce the body’s stress response.”

Even if it had no direct physiological merit, massage therapy would still remain valuable for its ability to temporarily distract clients from the outside world.

“Getting a massage helps me to stop obsessing over stressful situations,” Dr. Fowler says. “By making you more mindful of what’s happening in the present, massage removes your focus from whatever stressors you have. That change in focus alone is a huge benefit.”

Stress-Proofing Your Practice

Clearly, stress is both physiological and psychological in nature—and so is massage therapy. To maximize stress relief for their clients, massage therapists must therefore pay equal attention to body and mind. Being thoughtful about the following choices can be a good start:

Massage environment: Because she wants stressed-out clients to feel relaxed from the moment they enter her practice, massage therapist Jessica Ludwig, LMT, gives careful consideration to what they see, hear, smell and touch. “My color palette is blues and grays. Everything is very muted,” says Ludwig, owner of Massage and Wellness by Jessica in Virginia Beach, VA. “I use microfiber sheets. My table itself is memory foam. And then I have a heated massage pad with another cover over it that’s slightly quilted.”

Comfort is so important that she even makes her own face cradle covers out of polar fleece fabric. “I love to get massages, but I hate when the face cradle is really uncomfortable,” continues Ludwig, who also curates her own music playlists on Amazon Music and uses scents sparingly. “My playlists have a lot of acoustic guitar and I don’t use any synthetic oils or fragrances. I just add a few drops of essential oil to my massage oil for a really light fragrance. Nothing heavy.”

Tableside manner: Because psychology is outside their scope of practice, massage therapists can’t counsel clients about the stressors in their life. Nevertheless, they can help clients relieve stress by giving them a safe space in which to talk about them.

“I tell people, ‘I’m not that kind of therapist, but this is a place where you can drop whatever baggage you’ve been carrying,’” says massage therapist Susan Rissolo, LMT, owner of Stress Less Mamma in Wilmington, DE. “To me, massage isn’t just physical. It’s also emotional—a mental unburdening that helps you free up space in your head.”

Echoes Ludwig, “I like to ask people why they came in and what they want to focus on. A lot of times they’ll say, ‘Oh, I’ve been under a lot of stress,’ so I don’t ask a lot of questions or have a lot of conversation. But if the client wants to share, I let them.”

Massage technique: Massage therapists can maximize stress relief by thinking carefully about where and how they touch clients.

“If you have a client who has monkey brain—they can’t stop thinking and are really overwhelmed—then they probably need to just zen out. To me, that means slower and more rhythmic strokes to put them into a more relaxed state,” Kennedy says. “Stress might look different for someone else. If they’re low-energy, fatigued or depressed, you might want to add in quicker and more potent strokes.”

Meanwhile, think about what activities cause stress—working, for example, and driving—and focus your massage appropriately. “Most people have neck and shoulder issues because we spend so much time sitting in front of computers and holding our phones. So I like to spend a lot of time working on those areas,” Rissolo says.

Don’t forget the face, Ludwig adds. “I have a lot of clients who complain about jaw pain—which makes sense, if you think about it. When we’re stressed, we clench our jaw,” she explains. “So I love to spend a few minutes loosening up the pressure points in the face.”

Education: Massage therapists can help clients by giving them tools and strategies to manage stress in between appointments.

Both Rissolo and Ludwig use social media for exactly that purpose. Ludwig, for example, uses Instagram to share wellness tips while Rissolo has a YouTube channel where she posts guided meditations.

“As massage therapists, we can’t prescribe or diagnose. But we can have conversations about lifestyle to help people reduce external stressors,” Kennedy says. “For example, if someone says they’re having trouble sleeping, you might ask them if they’ve considered reducing their caffeine consumption. Or you might suggest some websites where they can read about sleep hygiene.”

Massage therapists also can make referrals. “Think about having a good referral network that includes counselors and psychologists,” Kennedy continues. “If someone needs additional kinds of therapy, you can refer those clients and become part of a larger care team.”

There’s one more thing massage therapists should prioritize to make their practice a stress-free zone, Ludwig and Rissolo agree: self-care.

“As a practitioner, you have to get your head on straight before you begin,” Rissolo says. “You can’t bring your stress into the room. Because if you’re stressed, your client is going to feel that.”